I don’t have much to say at the moment; it was lovely to meet folks I know only remotely and new folks I hadn’t known at all. Talks were a combination of inspiring and informative. Here are the slides from mine.

Author Archives: Michael Sokolov

Kayak launch day

It took me a couple of weeks to get the finish done. Coating the canvas with butyrate dope was pretty easy, although I learned that the ventilation in the converted garage room was not all that great, and ran around opening all the windows in the house to flush out the toxic fumes; not before I was discovered though. The thing that really took a while was the varnish I layered on top of that. The book proposed coating the transparent undercoats of dope with more layers of pigmented dope – paint, basically. But I wanted the my dye job to show through, so I was committed to use a transparent finish. I guess I could have just use more layers of dope, but I used a whole gallon on three layers, and this stuff was pretty expensive – around $80 for the gallon.

So for the final layers I used spar varnish, which is a heavy-duty traditional oil-based varnish. It’s also about $80/gallon at my hardware store, but I was able to apply three coats using only a pint of the stuff. Unfortunately the first coat I applied using some old stuff I found in the basement. It seemed OK underneath the top layer of hardened semi-gelatinous varnish, if a little dodgy. It was kind of thick, so I thinned it with some paint thinner and applied with a rag. It went on like runny snot and didn’t seem to want to dry. Maybe because the temperature dropped into the 40s and it was raining. Varnish likes it warm and dry. I ran the heater and the air conditioner (to pull moisture out of the soupy air), and kept on checking. After three days it was still kind of tacky. I rubbed it down with paint thinner, scraped off the worst bits of goo and bought some new varnish and Japan dryer, an additive that is supposed to help varnish dry in colder wetter conditions.

I think in the end it came out nicely, although it’s far from professional standard as such things go.

Its shiny!

Here’s a full view from the top. I’m pretty happy about the slightly irregular dye color.

And finally, it’s a she, and she floats!

How does she float? Well, I am really pleased. No leaking, that’s good. Much tippier than my old plastic tub, but I got used to this pretty quickly while paddling. The fit is kind of tight, but it seems right. I can securely brace my thighs against the Masik and paddle comfortably. After 45 minutes of paddling though my left foot was going numb. I have the same problem when running sometimes; bad circulation I guess. I hope that I will get used to the position, but we’ll see.

Generally speaking, she tracks quite well. Turning is a more deliberate process than with the flat-bottomed 9-footers, which spin like tops. There is a nagging tendency to pull to the left though, that really does need to be corrected. I think the stern piece must not be quite straight. So I’ll probably add a skeg, an external fixed rudder-like attachment, to get that worked out.

All-in-all a success! I look forward to many more days of paddling.

Skin-on-frame kayak, part 2

Steam-bending is a voodoo woodworking art. If you heat up wood, and it has enough moisture in it, the fibers will loosen enough that a previously stiff board can be bent into a new shape, which it will retain after cooling. At least some wood will. How well this works depends on a lot of factors including the species of wood, whether it is clean (without knots), whether the grain runs nicely parallel, how dry it is, whether it has been air-dried, or kiln-dried, how long you steam it, whether you pre-soak it, in water, or in water plus fabric softener! Some youtubers will tell you how easy it is, but even they keep extra pieces on hand for when they break one. Many years ago I had tried bending guitar sides over a hot pipe (no steam required), and that went OK, so how hard could it be?

I went to a specialty lumber store and bought some ash (kiln dried, as everything is that you buy at a lumber yard). I had read that ash was a good species for bending, even kiln dried. The gold standard for this kind of work is white oak, but supposedly only when it is green, or lightly air dried, and I just didn’t have access to anything like that. Following the book, I concocted a steam box from a sheet of styrofoam insulation and a lot of duct tape, and hooked it up to our old hot pot using some PVC pipe left over from a bathroom renovation.

I did some trial bending runs to get an idea how long I would need to cook the ribs and settled on something like 15 minutes. The idea here is to work efficiently by staging all the ribs, loading the steamer with a batch of 4 or 5 inserted at one minute intervals, and then inserting a new dry one at the left every time you take a cooked one out of the right.

I won’t go into the whole bending process itself – there are some great videos from pros out there you can watch if you care to. I’ll just say that it was nerve-wracking and fun, and it came out OK in the end, and even if some of the ribs did split out the grain here and there, nothing too terrible happened. One thing I might do different if I try this again though, is to pre-soak the wood. I decided not to this time, following the advice of one knowledgeable-sounding site I found. That guy had nothing but scorn for the idea. Now I’m not so sure – it might have helped. I had to apply a *lot* of pressure to bend these ribs, and I get the idea it should have been easier. You can see one of the several failed attempts at the bottom of the photo. The room smelled like hot styrofoam the whole time.

I won’t go into the whole bending process itself – there are some great videos from pros out there you can watch if you care to. I’ll just say that it was nerve-wracking and fun, and it came out OK in the end, and even if some of the ribs did split out the grain here and there, nothing too terrible happened. One thing I might do different if I try this again though, is to pre-soak the wood. I decided not to this time, following the advice of one knowledgeable-sounding site I found. That guy had nothing but scorn for the idea. Now I’m not so sure – it might have helped. I had to apply a *lot* of pressure to bend these ribs, and I get the idea it should have been easier. You can see one of the several failed attempts at the bottom of the photo. The room smelled like hot styrofoam the whole time.

The ribs outline the shape of the hull. Now we have really defined how the kayak is going to eventually sit in the water. Its hydrodynamic characteristics will all derive from this shape.

The next step is to fit out several longitudinal pieces: the keelson, which runs the length of the boat at its lowest point, and the chines, which run in parallel on either side. These all come together at the bow and stern where they meet two other pieces that form the pointy ends. The book had a fancy name for them, but for the life of me I can’t remember what it was. In this photo you can see the nifty lashing that holds these pieces to the ribs; the keelson is done, here, and the chines are being held in place with clamps while they are positioned for optimum boat shape (they will hold the skin just off the ribs).

Here’s the pointy end I was talking about.

Now it really looks like a boat! Just needs a few little odds and ends, and then a skin!

Oh I forgot to mention this cool part of the Greenland kayak design, the Masik. This is a curved piece of wood you brace your thighs against when paddling. I made this one out of a curved maple branch that fell off the tree in front of my house. You can see that tree’s shadow on the bricks there. It’s a giant, starting to die, but it still explodes in a riot of red, orange, and yellow every fall and buries us in its leaves. The piece I made the Masik from was starting to rot a bit, and it has some neat figure in the grain that I liked a lot. Shaping it was a fun challenge. I roughed it out with a chain saw and then went at it with a variety of hand tools. In this picture it’s still in a pretty rough state, but you’ll have to take my word, it worked out nicely.

Oh no! Somewhere along the way this gunwhale developed a nasty-looking crack. More fallout from forcing them into too dramatic a shape? Oh well, it doesn’t go too deep – I hope it’ll be OK? Better get the skin on soon, that should help to hold it together, right.

Oh no! Somewhere along the way this gunwhale developed a nasty-looking crack. More fallout from forcing them into too dramatic a shape? Oh well, it doesn’t go too deep – I hope it’ll be OK? Better get the skin on soon, that should help to hold it together, right.

I decided to skin the boat in canvas, and coat it with butyrate dope like an old airplane, in keeping with the generally old-fashioned gestalt. Sealskins seem to be out of fashion, and anyway, unattainable. Most people seem to use nylon at this point. It’s lighter and probably easier to coat since you can use something easier and cheaper like epoxy or urethane or some such thing. Cutting it is annoying though: you need a hot knife to melt the edges to prevent it from fraying. Canvas was fun to work with. I learned how to sew. A thimble was essential to get the big needle through several layers of the stuff. The thread is dental floss!

The whole process of stretching the canvas on, trying to keep as much tension as possible, was pretty fascinating. The traditional system is to lace up a very rough seam, like a giant shoelace, along the centerline of the deck, draw it tight, and then sew up with fine stitches. The book I was following had a different idea, which I tried, stapling the fabric to the gunwhales to tighten it, and then stitching along one side of the deck.

Oh I almost forgot to mention. There was this thing that drove me totally crazy right at the end of the project. Another steam bending step was required in order to create the hoop that forms the cockpit, drawing all the fabric together around the place you sit. The idea was to make this hoop by bending a single six-foot stick of ash around a form. I tried this three times and broke the darned thing every time. Maybe I didn’t steam it enough at first? This piece was bigger and thicker than any of the ribs. One time I think there was a weak spot in the grain. The bending itself is tricky – you are holding this thing under a lot of pressure, working under time pressure since the wood is only pliable for a short time after you take it out of the box. Finally, even the fourth time it broke, so I finally decided to make it out of two pieces, and glue them. Sigh, the only glue on the thing. But it got done

Once the stitching was done, and I had made the cockpit hoop, I died the fabric. You can see my first crude stitches on the stern before I figured out how to get the seam right on the corner.

Getting the skin stitched into the cockpit hoop was an exercise in trying to tension up the loose flaps in the middle of the deck. Following the system proposed in my book was pretty straightforward and a little magical; I drilled holes all around the hoop and stuck nails through the fabric just below the holes, levering them up and pushing them through in order to tension everything. Then I laced a length of cord through all the holes, removing the nails, and the twine draws everything up nice and tight. Here’s a picture of the hoop with the nails holding the fabric to it:

The last thing is to coat the whole job in cancer-causing chemicals to make it watertight. As I said before I’m using butyrate dope. This is the stuff you may have sniffed if you ever made a model airplane. It is a toxic stew of VOCs (volatile organic compounds) – basically every chemical ending in “-ene” is in there. I bought a respirator, don’t worry, my glue-sniffing days are over.

Next post should be launch day. I’m super excited to see if this thing actually floats, how tippy it will be and whether it will track straight. Oh and hmm I guess I’ll need to name it (her?). That will be the hardest part.

Skin-on-frame Kayak, part 1

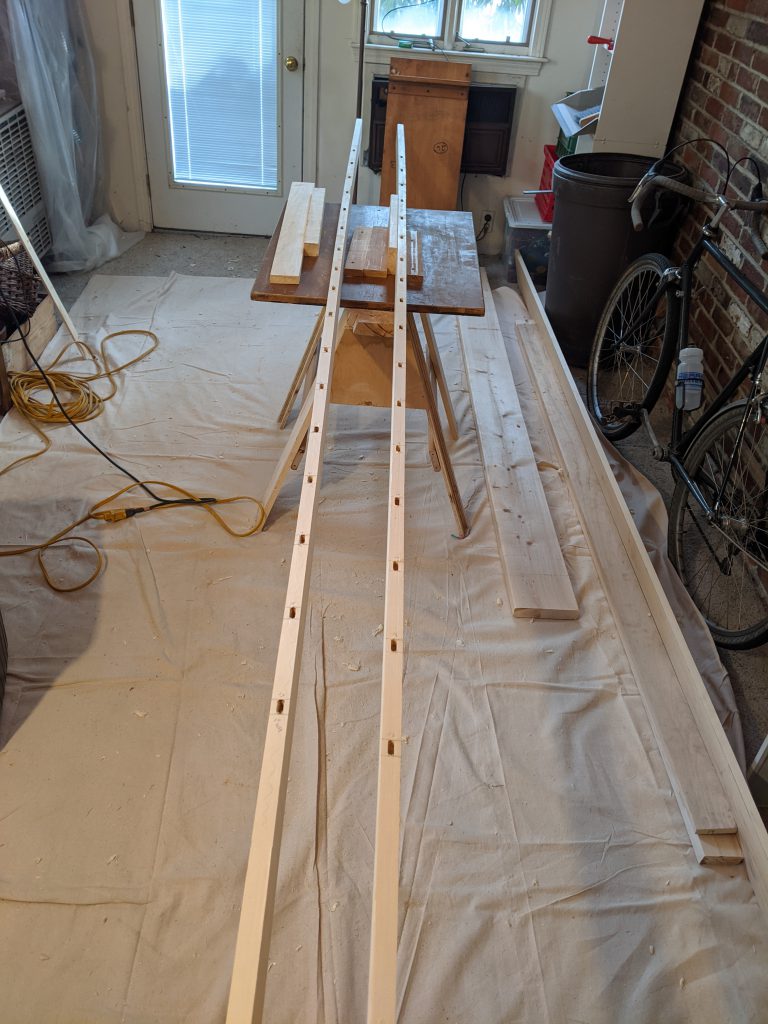

Before buying wood, I needed to figure out roughly how big a boat I wanted to make. The Greenland kayak design seems to be quite long and narrow – about three times your height, and barely wide enough to squeeze into, so for me that would have ended up around 17 feet (5m), and something like 20″ wide. I have been using a dinky 9′ plastic tub that is about 28″ wide, so this would be quite a leap. Besides, I don’t have anywhere to store a 17′ anything in my house, and don’t want to leave this labor of love outdoors where it would be subjected to the vagaries of New England weather. I settled on a 12.5′ length and 24″ wide. Maybe a little wide to roll, but since I’ve yet to learn how to do that and mostly paddle around in calm lakes and streams, this doesn’t seem like a big problem. Having settled that, I headed to the lumber yard to pick up some 2x construction-type softwood lumber that will make up the large longintudinal pieces: the gunwhales, keelson and chines, plus some clear pine for the deck beams and other assorted pieces. The ribs that make up the hull will be formed by bending them into shape and require some more specialized stock, and I haven’t yet figured out what to use, so those will be chased down later.

The first actual woodworking can begin! I needed to shape the gunwhales, which are the two large pieces, one on each side, that define the outline of the boat as seen from above (or below), and into which everything else will fit. I ripped these in the driveway using a circular saw and a simple jig to keep it aligned reasonably well:

hm, I guess the blade slipped a bit while resawing to 7/8″ thickness using the circular saw.

It’s important that these two pieces are cut from the same board and have the same dimensions. The symmetry of the boat will rely on their being held in opposing tension, so they need to behave similarly. I was a little worried about that wandering sawblade cut, but hoped it wouldn’t compromise the form too much! The first of many deviations from perfection, sigh.

Someday maybe I’ll acquire a machine planer, but I haven’t been able to justify it yet. And it’s still a pleasure to hand plane such clear pieces of softwood with a nice sharp blade. Here they are starting to look pretty clean after the saw marks have been removed. The ends of the gunwhales get tapered and shaped in the ends where they will rise up.

I splurged and bought this antique compass plane on E-Bay to shape those inside curves. This is an amazingly clever tool; its sole can be adjusted to a range of different curvatures. The one I got was probably 100 years old, but still in great condition. Whoever sold it had even kept the blade sharp, so I didn’t even really need to touch it up before using it!

Next, I measured and marked out the locations for all the deck beams and ribs. I love this marking tool: it makes it easy to get the same distance from the edge every time, and even has a two-point setup so you can mark both sides of the mortise at once.

Then I cut the mortises for the ribs using a router with a jig to enable me to reliably and fairly quickly make the same cuts. The mortises for the deck beams need to be cut at a compound angle, so they will be done later using a less automated process, once the shape of the gunwhales is defined.

The rib mortises came out pretty nice

The form of the boat is defined using plywood stretchers that hold the gunwhales. I think this process was designed for a much longer boat which would have had a gentler bend. In this form factor, the pressure on the gunwhales was pretty intense, and it was hard to get the forms to stay in place. The one in the foreground below really wanted to slip forward. I was consumed with anguish for days worrying that I had veered too far off the plan I was following. One concern I had was that the gunwhale tips didn’t meet at a sufficiently acute angle. They were expected to end up nearly parallel, but in my setup they left a pretty gap where they met, as you can see below.

After mighty struggles to force a tighter shape into the gunwhales, I finally decided to relax and let the wood dictate the shape. I added a breasthook to hold everything together in the stern. Cutting the compound angles on that block was a fun challenge.

After mighty struggles to force a tighter shape into the gunwhales, I finally decided to relax and let the wood dictate the shape. I added a breasthook to hold everything together in the stern. Cutting the compound angles on that block was a fun challenge.

Here is the boat really beginning to take shape, with all its deck beams in place. The curved beams are raised up to allow space for the paddler’s legs. This is going to be a pretty tight fit! You can see the variety of clamping systems I used to hold everything together. I had some major issues getting to this point. When I first tried fitting everything together, some of the beams were too short, or maybe the others were too long? I had measured so carefully! What went wrong there I’m still not entirely sure. I think maybe the shape changed while I was measuring? It was under so much tension, and possibly not held completely still. I had to re-cut some of the beams to get them to fit.

Another significant challenge was ensuring the symmetry of the arrangement. The whole setup did have a tendency to rack and twist ever so slightly, and if I didn’t correct for that, I would end up with a crooked boat that wouldn’t track straight. Again I think a lot of these issues resulted from having shortened the boat from its original design. If I did this again, I might consider using beefier spreaders, or some other system for shaping the gunwhales.

In the end the line I ran from end to end settled over the previously-marked midpoint of the center beam pretty well. Off by less than 1/8″ over 12′ – I’ll take it!

One more photo of this stage, after pegging and lashing the ribs in place and removing the clamps:

One more photo of this stage, after pegging and lashing the ribs in place and removing the clamps:

This was a major milestone, time to take a break. When we come back, it’ll be time to steam-bend the ribs!

Skin-on-frame Kayak, prelude

I’m reviving this blog years because I feel like sharing a project I’ve been working on: building a skin-on-frame kayak. I don’t propose to teach how to build a kayak; I’m just learning! Nor is this a history of The Kayak. This is a personal journey of escape and discovery. I will share what I learn, the mistakes and struggles. Hopefully it ends with me in a boat on the water. Maybe I’ll even learn to roll it. I hope folks will find this interesting. For me it has been truly life saving.

[Note: about this blog, and comments. No more comments 🙁 I would love to get your comments! But the internet does not make it easy. When I last checked I had almost 100,000 spam comments, and I don’t want to devote my life to defeating spam. So … if you want to reply to me, send me a note on twitter, where I am @msokolov].

I was largely working at home before the Pan***ic started, so at first I hoped it wouldn’t make all that much difference to me, but after months of basically never going anywhere except upstairs and downstairs, and occasionally out in the yard to fill the bird feeder, my life started to feel pretty low-dimensional. Eat, sleep, crap, work, rinse, repeat. Shower occasionally, and maybe cut my own hair. I think we’re all living some version of this. So I started coming up with stuff to do at home. Picked up the piano again, played some video games, but I found myself dreaming about a life out of doors.

I’m not sure exactly where I got the idea to work on making a kayak. Maybe because my daughter has been working on a fantastic boat restoration project. Maybe because a boat fantasy is a pretty good way to dream of a life of adventure while cooped up indoors during a New England winter during a raging pandemic. For whatever reason, the idea of building a boat crept up on me until it seemed I just had to do it. Over the years I’ve leveled up my amateur woodworking skills and tools, so I managed to convince myself I was ready for some kind of boatbuilding project, but I wanted to find something on the right scale, and a kayak is just about the smallest watercraft there is. Its prehistoric roots also gave it an appealing glamor. Early Americans made kayaks from driftwood, bones and animal sinew that were sturdy enough to use for hunting whales in the open ocean! Surely with modern tools I could accomplish something that wouldn’t sink?

I started by clearing out our semi-finished garage-turned-extra room and buying some books. Cleaning out the room rapidly devolved into a yak-shaving exercise. Where would all the stuff go? This included some large family heirlooms, a guest futon couch, a big piece from our youngest daughter’s senior thesis project, and these larger encumbrances were surrounded by the other more minute detritus accumulated over the years in this out of the way corner of our house. I am pretty ruthless about throwing things away, but a lot of this stuff needed to stay. What about the family VHS collection? Disney – in the trash. Unlabeled VHS cassette? It might have somebody’s birthday on it! I made a box to send to a digitization service some day. It was a challenge not to become overwhelmed by all the stuff. At one point, I thought I might pull up the ratty old carpet and tear down the sagging ceiling. I fantasized about trash bags full of plaster and watched online videos about pulling up carpet tacks. In the end I decided none of this was essential to my project though. Happily I was able to repurpose some of the items for use in my new workspace. Here’s a glimpse. At least I would have decent light, especially after rewiring some defunct standing lamps we had stashed away in the basement.

The workspace

I bought a random sampling of how-to books about kayak making. There has been an explosion of books in this area: apparently I’m not the only one with this itch. The one I ended up settling on as a guide was Building the Greenland Kayak, by Chris Cunningham. This book’s esthetic appealed to me, as did its detailed instructions. The kayak design it presents is (I believe) closely copied from traditional models in its shape and parts. The ribs that form the hull are bent wood, and the joinery is all dowels and lashings; no glue or screws are used. The materials called for are adapted somewhat for modern usage, mainly in the covering, which is not going to be sealskin, but nylon or canvas (I chose canvas). Cunningham also presents various construction techniques adapted for whatever power tools may be available. He indicates possible approaches using only hand tools at every step, but it certainly would be a lot more work to mill the long stock without a circular or table saw. Apparently one traditional method of making ribs flexible enough to bend was to chew on them. I opted to save my teeth and make a steam box.

Another book I enjoyed reading on the subject was George Putz’ Wood and Canvas Kayak Building. This book is encrusted with salty Maine wisdom! I think its designs are less fussy to build, and probably a bit more comfortable, if heavier, than the bent-rib Greenland variety. Rather than bent ribs for a frame, Putz’ boats deploy a trestle-like amalgamation of cross-members along with floor “timbers” for their hull, and he has no pretense of traditional construction, relying on screws, glue and other fasteners throughout. I might try these ideas next time. I also consulted Fuselage Frame Boats, by Jeff Horton, which presents yet another approach to wood kayak construction; plywood frames to shape the hull (the fuselage).

Finally I should mention Brian Schulz of Cape Falcon Kayak. I chose not to enroll in Brian’s course or buy his plans, but I did learn a lot from the videos he has posted online, especially his excellent advice about steam bending.

I have lots more to say, but not today. Next time I’ll start gathering materials and making the first cuts.

Site migration

OK it’s 2018 and it is officially time to stop hosting blogs in your basement. I’m moving this blog and various other stuff out of my laundry room server and into the cloud.

The move promises to replace the nagging fear of attack by bitcoin miners, death by power outage, hard drive failure, or flooding with a $3.50/month bill. That’s what AWS Lighstail hosting costs today for its very lowest tier. I also plan to restore my vanity email domain using this server, since for a few years now I have been unable to maintain that at my house due to Verizon’s SMTP port blocking. I’m also planning to move some larger archives (music, pictures, etc) to S3 and relay them here using S3-FUSE. I think this micro-host might just be enough.